By Mark Preen, China Briefing, Dezan Shira & Associates

The scale of China’s urbanization over the past four decades is a staggering feat in human history.

In 1978, the year in which China started its policy of ‘reform and opening-up’, the urban population was just over 171 million – 17.9 percent of the total population. In 2016, the urban population was nearly 783 million – 56.8 percent of the total population.

However, history is still in the making as the country’s urban population is on course to hit the one billion mark by 2030.

The government is taking a leading role in supporting this urbanization. One of the primary reasons for this is because research shows that a country’s urbanization level is correlated with its level of economic growth.

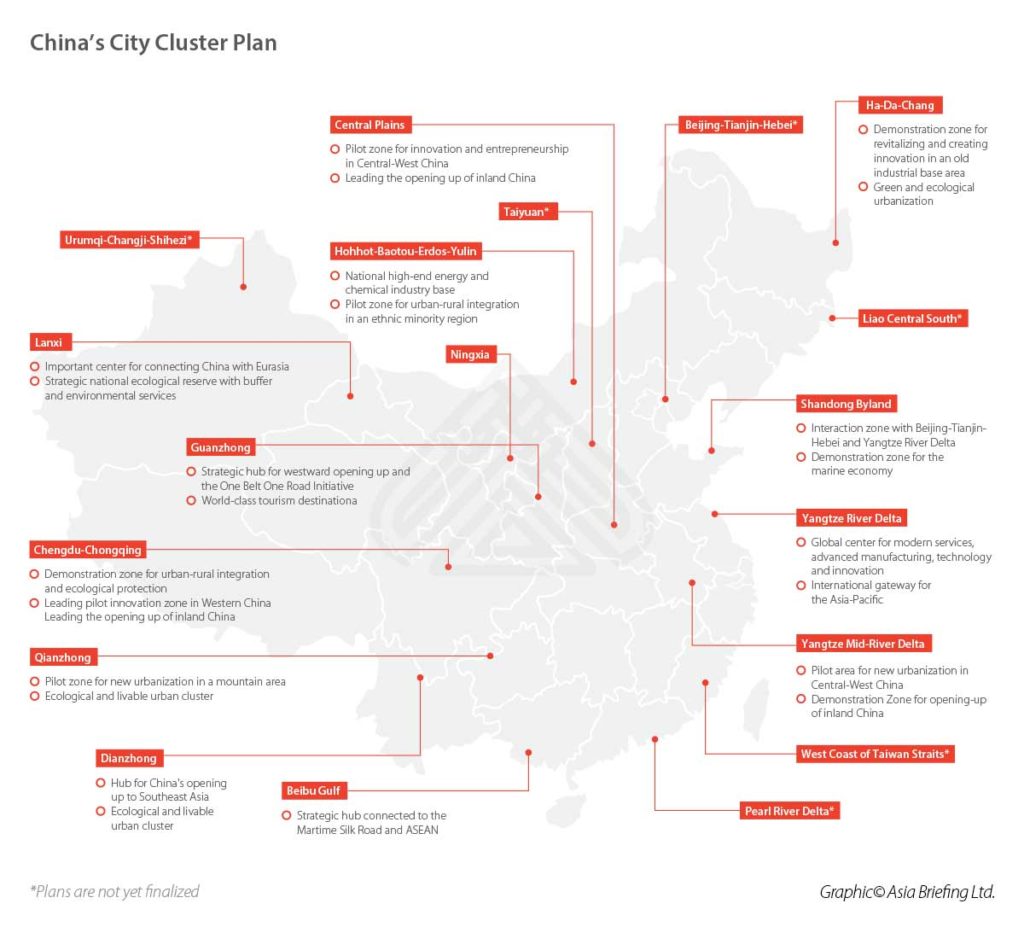

The city cluster plan

Of the 19 city clusters, the central government has prioritized three of them to become world-class clusters by 2020. These three clusters, in the Pearl River Delta, the Yangtze River Delta, and Beijing-Tianjin-Hebei, will

be the most innovative and internationally competitive of all the clusters, and thus drive national economic development.

The other 16 clusters will have relatively less economic clout. These other 16 clusters can be classified into eight medium-sized and eight small-sized clusters.

Medium-sized clusters each comprise about 3 to 9 percent of national GDP and focus on driving regional economic development. Meanwhile, each small-sized cluster is equal to or less than 2 percent of GDP and focus on driving provincial economic development.

It is likely that two of the eight medium-sized clusters, the Yangtze Mid-River cluster and the Chengdu-Chongqing cluster, will eventually graduate to join the ranks of the three world-class city clusters.

Furthermore, the combined economic contribution of the country’s clusters is astounding.

In 2015 China’s 11 largest city clusters accounted for one-third of the country’s population and two-thirds of its economic activity, according to the Asian Development Bank. Meanwhile, The Economist reports that the 19 city clusters account for nine-tenths of the country’s economic activity.

Although each cluster is ambitious in its own right, the government plans to link the clusters along ‘two-horizontal and three-vertical’ corridors. The ‘two horizontals’ are the Land Bridge Corridor in the north and the Yangtze River Corridor; the ‘three verticals’ are the Coastal Corridor, the Harbin-Beijing-Guangzhou Railway Corridor, and the Baotou-Kunming Railway Corridor.

To extend the international influence of China and its clusters, one of the horizontal corridors and one of the vertical corridors will be linked to the Belt and Road Initiative. The Yangtze River Corridor will be linked to the land ‘Belt’ section, while the Coastal Corridor will be linked to maritime ‘Road’ section.

Reasons for the city clusters

Although city clusters are not unique to China, the sheer scale of the government’s ambitions for city clusters are beyond those of any other country. The average size of the five biggest clusters in China is 110 million people, which is almost triple the size of Tokyo, the biggest city cluster currently in the world, with a population of 40 million.

Some of the reasons for using city clusters in China are also specifically relevant to the country’s new and current stage of economic development. The government recognizes that the economy is slowing down, and to sustain the economy, it needs to rebalance away from a reliance on export- and investment-led growth, moving towards consumption-led growth.

City clusters and its intended urbanization may help because urban dwellers with higher incomes generally consume more than rural dwellers. Clustering can also increase China’s productivity and innovation by grouping more firms and increase the size of the labor market.

Well-connected infrastructure and transport facilities are vital to this because the effective size of a labor market is defined by the average number of jobs accessible per worker in less than a one-hour commute.

The integration of clusters with more developed hubs, and less developed peripheral cities, may assist China with its policies of supply-side reforms and high-quality growth. Through clustering, resources will be reallocated from bigger cities to smaller cities.

This will allow smaller cities, which tend to be at earlier stages of industrialization, to move up the value chain and away from heavy polluting industries, while bigger cities can move further up the value chain by focusing on innovation and the Made in China 2025 industrial strategy. The free trade zones (FTZs) will also assist the bigger cities in attracting more innovation-based investment.

Question marks around the city clusters

Due to the size of the clusters, each cluster will require effective coordination involving different levels of government.

The plan is for central government to be more responsible for inter-provincial coordination, while provincial governments will be more responsible for intra-provincial coordination.

However, there are concerns that cluster-wide coordination will be difficult, especially in the short run. One of the main causes for concern is that there is a tradition of municipal and provincial governments competing for projects and investment opportunities. More regional governance is therefore needed. In the case of the Yangtze River Delta cluster, for example, the authorities of Shanghai, Zhejiang, Jiangsu, and Anhui agreed on a three-year action plan for 2018-2020, and launched the Collaborative Advantage Fund to manage resources.

Some sceptics also think that the government’s plans are unrealistic. For example, there are concerns that the labor market of each cluster will not actually be as populous as planned because high-speed train stations are usually far from city centers, which means travel between cities in a cluster can be more than one hour.

Further, the government has only completed plans for 12 clusters – the remaining plans expected by 2019. Even the exact number of clusters is not clear – some sources report that planning could be extended to as many as 22 clusters.

Despite these concerns, China has a record for historical development achievements, and achieving these records in its own unique way. One only has to look at China’s urbanization over the past four decades.

Although investors should approach clusters with caution and diligence, they should also recognize that clusters should be taken seriously – there are a lot of potential opportunities in China’s next phase of urban development.

This article was first published on China Briefing. Since its establishment in 1992, Dezan Shira & Associates has been guiding foreign clients through Asia’s complex regulatory environment and assisting them with all aspects of legal, accounting, tax, internal control, HR, payroll, and audit matters. As a full-service consultancy with operational offices across China, Hong Kong, India, and ASEAN, we are your reliable partner for business expansion in this region and beyond. For inquiries, please email us at china@dezshira.com. Further information about our firm can be found at: www.dezshira.com.