Written by Out-Law, Pinsent Masons

There has been a significant increase in the number of unsolicited proposals (USPs) for greenfield and brownfield public-private partnership (PPP) infrastructure projects in Asia over the past two years.

Unlike solicited proposals where a government entity launches a formal public tender, in the case of an unsolicited proposal, it is the private developer who first approaches a relevant government entity with a proposal to develop a particular infrastructure-related project. In many cases the proposal will be for a project that is not in the government’s then contemplated pipeline but is one where the private developer nonetheless sees a viable business opportunity.

USPs are seen by the public sector as helpful in addressing the need for infrastructure projects to be undertaken in circumstances where those projects might not be developed on a timely basis or even at all under a traditional procurement process. This is often attributed to institutional deficiencies or challenges related to framework or capacity.

Private entities, on the other hand, are willing to invest often significant time and resources in developing an unsolicited proposal in the hope of landing lucrative project development opportunities. There is an element of risk in doing this, though, because it is an inherently speculative approach.

Emergence of USPs in Asia

There is strong investor appetite for greenfield and brownfield infrastructure opportunities in Asia, while emerging markets often struggle to close competitive public tenders successfully and on time. These factors are driving private entities to submit USPs as one way to satisfy investor appetite.

What is perhaps surprising is that several regional governments are proactively, but often privately, recommending that companies initiate projects as USPs. Reasons cited include lack of government budget to run solicited project procurement; absence of capacity within the relevant government agency to handle such procurement, and a desire to avoid the bureaucratic infighting that sometimes characterizes the solicited procurement process.

The unsolicited route has recently started to get some traction in Indonesia, the Philippines and Vietnam, selectively. By definition, these projects tend to be ‘under the radar’ and only come to light if action is taken by the public body. That might be a Swiss Challenge, where third parties are invited to bid for work in a project that initially came to them via a USP. By this time the originating proposer has usually invested many months of work into developing the business case for the government.

-

The World Bank Group authorises the use of this material subject to the terms and conditions on its website.

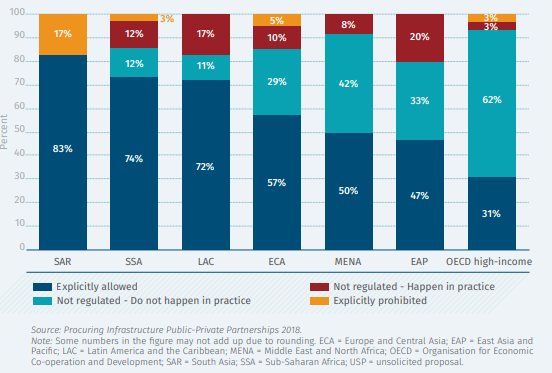

In a 2014 World Bank study more than 85% of the countries reviewed, including those in Asia, Africa, Latin America and the Caribbean, have accepted USPs in a number of ways. The same 2014 World Bank study also showed that more than 70% of countries have already developed formal legal frameworks to handle USPs. For most countries with PPP laws in place, they have also supplemented those laws with additional laws regarding USPs. These statistics therefore evidence the emergence of USPs, in Asia, in different ways.

Issues that may arise

In the context of Swiss Challenge arrangements, many issues can deter other serious bidders from launching competitive bids and therefore undermine the relevant public tender.

For instance USPs often lack transparency and trigger concerns about corruption. Lack of preparation time is another issue, when a government runs a public tender but fails to provide adequate time for the non-originating bidders to prepare competitive bids. Another deterrence specific to the Swiss Challenge is the right for the original proponent to match offers.

Certain situations will also exclude the need to hold competitive tenders and in these circumstances the government can negotiate with the original proponent directly. These situations include where the original proponent owns rights to the only practicable land for the project, and where the project involves specific technology or proprietary rights available only through the original proponent.

Challenging, but here to stay

USP initiators have to handle at least twice the amount of work involved in solicited bidding, not least because they will handle many of the usual responsibilities of the relevant government entity, including:

pre-feasibility and full feasibility studies;

developing full business cases on behalf of government and in many situations;

drafting the entire suite of tender and concession related documentation;

competing in a bid scenario.

It is therefore not for the faint of heart or those with thin resources. But it does seem to pay dividends for those willing to make these efforts, at least empirically-speaking.

PPPs are just way of addressing the infrastructure needs across Asia. In that context, there should be recognition and acceptance that USPs do exist in Asia and have a place in the procurement of infrastructure projects.

Additional reporting: Benedict Tse

Source: Written by Out-Law, Pinsent Masons

Author: James Harris, Partner, Pinsent Masons